The most important thing to look for in a therapist

Montreal physiotherapy

Here is the most important thing to look for when meeting your physical therapist, osteopath, or healthcare practitioner for the first time.

Therapeutic alliance.

The therapeutic alliance is your relationship with your therapist. It is how you connect and communicate with each other. It is the soul-to-soul understanding that is vital for your recovery.

No matter how experienced, knowledgeable, and highly recommended a therapist is, you will never be able to achieve your goals without a therapeutic alliance.

Imagine this: you go see an optometrist because you’ve been having trouble with your eyes. After listening to you for a few minutes, he takes off his glasses and offers them to you.

“I can’t see anything!” You would likely exclaim.

“That’s weird”, he responds. “They work great for me, I’ve used them for 20 years!”

Any possible treatment offered by a therapist is unlikely to work if there is no proper understanding of not only the condition but the patient who has the condition. This is only possible through therapeutic alliance.

The therapeutic alliance is fueled by trust and the desire to attain a common goal.

How I achieve a therapeutic alliance with my patients

I tell my interns that achieving a therapeutic alliance with their patients is the most important thing they can achieve during their first visit. Unlike the exercises and manual therapy techniques they learn in classes, however, there is no reliable technique to build a strong therapeutic alliance with patients.

From my experience and from Stephen Covey’s renowned book “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People”, I have found empathic listening to be most effective in building a strong relationship and therapeutic alliance with my patients.

It goes beyond classic listening strategies such as active listening and attempts to get inside the other person’s frame of reference: how they see the world, how they perceive their problems, what are their deepest concerns, and what they believe they need.

Note that empathic listening is not about automatically agreeing with everything the patient says in order to deceive them into a therapeutic alliance. The goal is not for me or anyone listening to my advice to become a “yes-man”; after all, the patient is here to listen to our professional opinion and evaluation.

This is why during my first session with a new patient, I always ask them questions such as “What do you hope to get out of today’s session?”, “What are your expectations from me?”, “What do you think is going on with your body?”.

As a physical therapist, I aim to understand my patient’s bodies but also their mind. Empathic listening puts the power in their hand to interpret their own conditions and what they believe would help the most.

Read article

How I overcame my own back pain and sciatica when deadlifting

Montreal physiotherapy

Intro

This article is very personal to me. It is about how I treated my very first patient: myself. It details my 7-year-long journey fighting low back and sciatic pain with deadlifts. In those 7 years, I have injured myself 3 times deadlifting. I will talk about what I tried and ultimately, what my treatment plan was. The reading may be quite bleak at first but stick to the end for the good ending and the valuable lessons I learned.

The initial injury

This all started when I was 18. My father had introduced me to the gym about 2 years ago and I had been going regularly. I was given a few reminders about safety, shown how to do some exercises and how I could use Google to look up any exercises I was unsure of, then left to my own devices. Things were going swell so far: I was getting stronger and had developed a passion for the gym. It was a way for my awkward teenager self to feel like he was improving himself, at least until I had my first injury.

During a set of deadlifts, I felt a sharp stab in the center of my low back and I dropped the weight and stood upright. Something was wrong.

How this affected me

Physically speaking, I was not in that bad of a state. After having seen numerous low back pain patients as a physical therapist, my symptoms back then would definitely be considered quite typical by my current standards. For an 18-year-old with no knowledge of physical therapy and who just had his first “serious” injury, however, I thought the world was ending. I felt a hard knot in my back at all times, and it was worse when I was sitting. This was awfully inconvenient since as a CEGEP student, I had to spend many hours at a time sitting to study and do my exams.

The largest impact this injury had was mental, however. The gym no longer felt like a safe place: it felt like a danger zone where any exercise was a trap that could make my back seize up.

I needed help. I could no longer do my favorite sport and could barely tolerate sitting for longer than an hour.

What I tried

As most would, I decided to go see my doctor. I was told to “lift with my legs more”, which was advice I had already heard before and didn’t address the current pain I was in. To his credit, he did refer me to go see a physical therapist, but I was too stubborn at the time to follow that advice. I thought the pain would just leave on its own.

I also went to an athletic therapist who massaged my back. This helped decrease the pain which was very valuable during the exam period, but the pain came back after a few weeks.

My physical pain did end up leaving on its own after 4 months, but my fear did not: for the next years, I was afraid of going back to the gym. Eventually, I did restart working out when I started my undergrad, but I completely avoided any leg exercises for fear of having pain again.

The re-injury

Skipping ahead 3 years into the future: I was now 21 and in my 2nd year of undergrad. My back pain had been on and off. It was never as bad as when I first injured itself but it still came back whenever I spent a long time sitting. I was still far from being a physical therapist but knew that it was possible for me to “treat myself” and to return to deadlift progressively. After obtaining advice from friends with more experience working out, I decided to start deadlifting again.

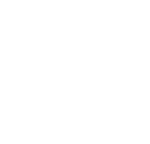

Things went well at first. My weights were going up week by week. Unfortunately, things went downhill when in the middle of a deadlift rep, I felt a great pulling in my right hamstring followed by immense pain. This was even worse than my back pain. I stood still in the middle of the gym for a few minutes, catching my breath and moving very slowly. I then mustered the strength to ask another gym member to help me unrack the weights and put the barbell away before I went back home.

Despite the more severe onset, I knew that this new injury was not as bad as my first one. It did not take a physical therapist to know that I had torn my hamstring and that I would recover much faster than my back pain.

My pain left after only a week but my fear of deadlifts came back with a vengeance.

“Maybe deadlifts are just not for me”, I thought. And so, like when I was 18, I continued working out but resumed avoiding this exercise.

The most recent episode

My latest injury when deadlifting happened when I was 24. I had been working for half a year as a physical therapist and was starting to get more and more comfortable treating low back pain, one of the most common reasons for patients to consult in physical therapy. I had even had the chance to treat patients with the exact same problem that I had: back pain when deadlifting.

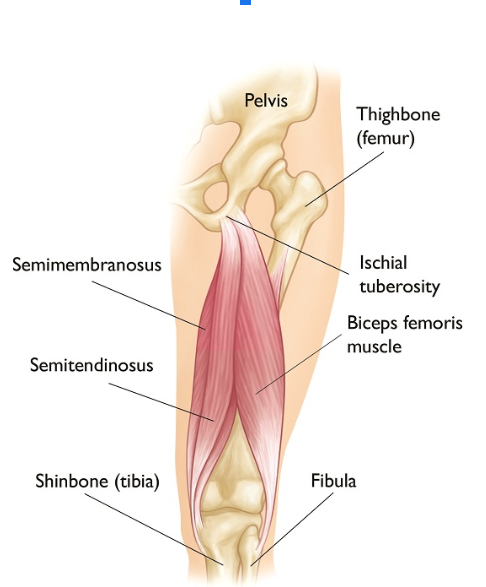

On my 2nd day of doing deadlifts, despite doing so with a low weight compared to my other exercises, I started feeling a pain of 6/10 (10 being the worse). Not just back pain, however, but a pain in the right side of my low back which radiated down to my right thigh: a sciatic nerve distribution, also known as sciatica.

Out of my 3 injuries deadlifting, this was clearly the worse. Not an isolated back pain or hamstring strain, but a pain that involved a nerve.

But this time, I had no fear. I knew exactly what this was and had helped patients overcome it. So why not me?

Why did I want to deadlift so badly?

Before we dig into my self-treatment, let’s address the question of why I kept deadlifting. Why did I keep doing this exercise? Didn’t I learn from the first injury, let alone the second? There is no shortage of exercises to do at the gym, why keep doing this one? 3 reasons.

I loved weightlifting and followed bodybuilders and powerlifters religiously. I also talked about weightlifting very often with my friends who were similarly passionate. Deadlifting was often a topic of discussion. The deadlift is one of the main lifts in powerlifting and one of the most effective muscle-building exercises for bodybuilders. I did not want to miss out on this exercise.

I wanted to deadlift because I was afraid of it. Even before becoming a physical therapist and making it a core aspect of my practice, I felt deep down that I had to conquer my fear of deadlifting.

The third reason had everything to do with me being a physical therapist. I always told my patients that I wanted them to be able to resume their activities but also to do the activities they were afraid of due to their pain. It is one thing to get other people better but another to get yourself better. I wanted to put my abilities to the test. If my treatment methodology was so good, surely it would work on me.

My rehab plan

My treatment plan, as with all my treatment plans for my patients, had 2 components to it: therapeutic education and exercise prescription.

Therapeutic education: In my first 2 injuries, I had fear. A fear of making things worse and injuring myself further. In my latest injury at 24, I also had that same fear, but I could replace that fear with knowledge. As a physical therapist, I had a battery of tests I could perform on myself. These tests showed that although my mobility and strength were diminished since the injury, most of my baseline measures were normal. This “self-education” along with the knowledge that I had gotten patients who had far worse symptoms than me back to deadlifting pain-free took me out of the fear mindset and into the rehab mindset.

Exercise prescription: I was going to get better, I had no doubt about that. If I stopped deadlifting and rested, I would very likely be back to normal in a few months. But that wouldn’t solve the problem: I would always have that fear of deadlifting. To overcome this, I had to get moving. So I prescribed myself an exercise protocol.

Finding my directional preference

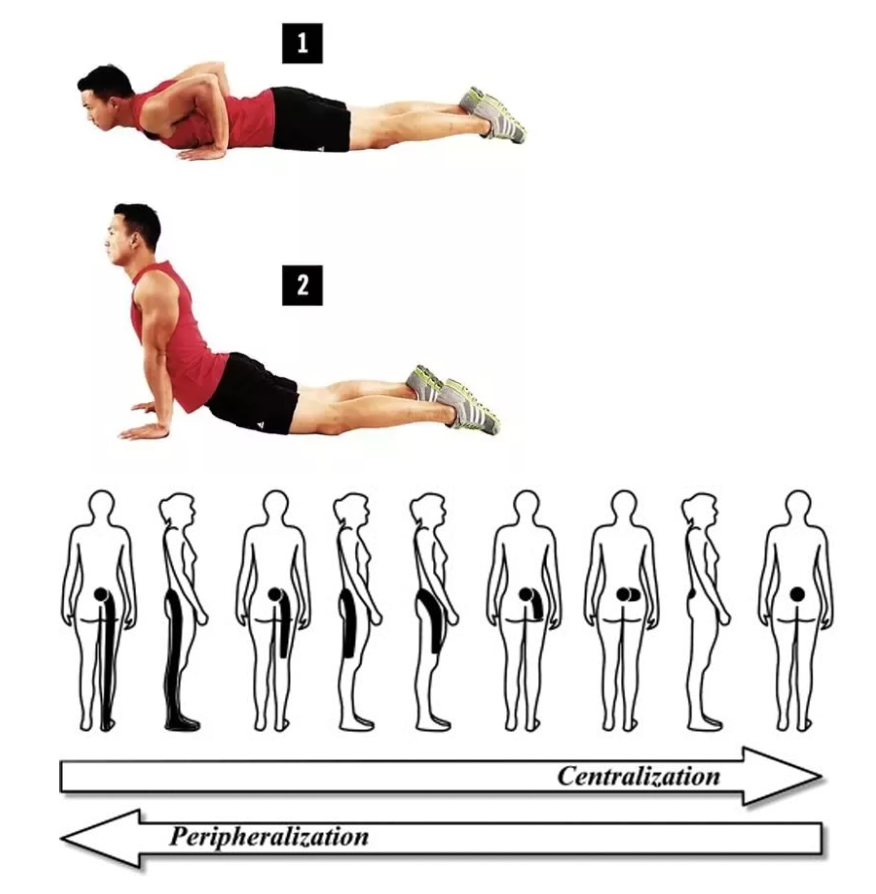

My first step was to identify my directional preference. The directional preference is a movement or position that, when executed at the right frequency and intensity, helps quickly relieve pain. In the case of sciatica where the pain was spread from my right lower back to my right thigh, my directional preference also had to centralize my pain.

Centralization is “a phenomenon where pain originating from the spine and referred distally, moves or retreats back towards the midline of the spine in response to repeated movements or guided positioning” and “in patients with sciatica, centralization was common and associated with improvement in activity limitation and leg pain” (from Centralization in patients with sciatica: are pain responses to repeated movement and positioning associated with outcome or types of disc lesions?).

This may be an overdose of scientific information, but I promised that I would be giving you all the details!

To find my directional preference, I identified baselines, namely my pain’s location, and tested a few exercises. The ones that significantly decreased and centralized my pain were repeated cobras, and so I continued doing it. For a complete explanation of this process, please read Mrs. O.’s case study.

Getting stronger

After a few days of doing cobras, my sciatica was not entirely gone, but it had centralized to my lower back and was now a 3/10. It was more tolerable and less worrying. More importantly, I now had control over my pain: I could do the cobras in case of any flare-ups. And so, I started the strengthening phase of my exercise program. The selection of exercises followed the principle of load management.

Conventional deadlifts were still painful for my back, so I replaced them with sumo deadlifts, which involved the legs more and my back less. Thanks to sumo deadlifts, I could strengthen myself in this movement pattern without provoking any symptoms, and regain confidence in lifting from the ground.

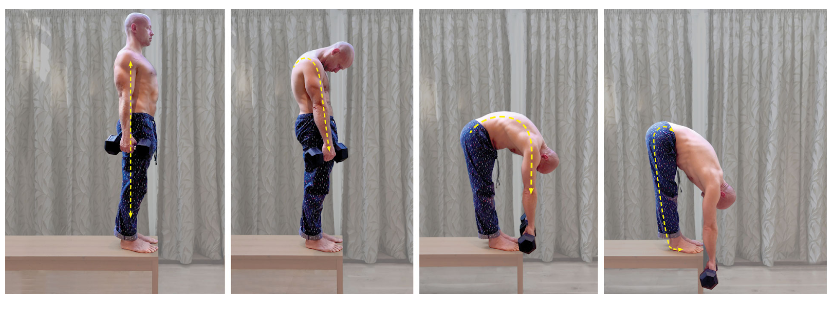

After 3 weeks, my back pain was mostly gone in my everyday life and I was getting closer to my pre-injury state. I knew that I had neglected to strengthen my low back extensor muscles, so I added 2 more exercises to my program: good mornings and Jefferson curls. These 2 exercises were great for my posterior chain, but also to reintroduce my back to pull the weight up with low loads.

The biggest benefit was that being able to perform these exercises helped restore my confidence in my back’s ability to support weights. This confidence grew every week as I increased my weight.

Returning to deadlifts and dealing with setbacks

After 2 months of doing my exercises, I decided to confront my demons: conventional deadlifts. As with almost anything in life, things did not go as planned. My pain had not magically disappeared and I was not suddenly capable of deadlifting Herculean weights with zero pain. My pain still woke up to a 2/10 during my last set of deadlifts.

I dealt with this pain by performing my directional preference exercise (cobras), which abolished it completely. I then waited a few days and then did deadlifts again. It was not instantaneous, but my progress was consistent: week by week and set by set, my pain was going down. 3 months after resuming deadlifts, the weight was now heavier than it was when I injured myself and I had no more pain deadlifting.

Performing an exercise at a reduced load and with tolerable pain is the essence of load management rehabilitation. By making sure that my pain was always Good Pain and that it remained in my control, I slowly got better with deadlifts until I had no pain at all.

Now

At the time of writing this article, it has been about a year and a half since my recent injury and I have been deadlifting for over a year now with no issue. I’m pulling a lot more weight than I did at each of my injuries. More importantly, this is the longest I’ve ever gone without injuring myself. Deadlifts (along with squats) are now by far my favorite exercise to perform at the gym because they make me feel good. They not only help me get stronger, but also remind me how far I’ve come, both as a patient and as a physical therapist.

Lessons learned

Despite not being a physical therapist yet, I was my first patient at 18. But my treatment, which consisted of avoiding the gym completely out of fear and waiting for the pain to leave on its own, was utterly terrible. I went over 6 years without addressing the root cause of my problem.

If you suffer from a similar problem, don’t be like me! Don’t wait 6 years before seeking help. I would love to guide you on your path to a full recovery.

Rehabilitation is not a miraculous and instantaneous process, even for a physical therapist. It requires dedication, hard work, and problem-solving, but is extremely rewarding.

It is more sustainable, effective, and ultimately pain-relieving to address the root cause of your pain rather than avoiding things that are painful.

References:

Albert, H. B., Hauge, E., & Manniche, C. (2011). Centralization in patients with sciatica: Are pain responses to repeated movement and positioning associated with outcome or types of disc lesions? European Spine Journal, 21(4), 630–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-011-2018-9

Images courtesy of: Foothills Sports Medicine Physical Therapy, Stickertalk, Ortho Info, News-Medical, Quora, Bodybuilding.com, Coach Mag, Gymnastic Bodies, ProActive Spine & Joint, my camera roll